YEARS AFTER: Achebe, His Works And History

By: Dan Ugwu

March 21st, 2019 was the 6th anniversary of the death of Chinualumogu Achebe, a novelist and essayist, a man of ideas who bowed to the invitation from the Elysian Fields at 82 on March 21, 2013 at a hospital in Massachusetts, USA. Achebe died with the burden of a seer, a change agent whose literary pouch brims with warnings that can chart a new course for national rebirth.

March 21st, 2019 was the 6th anniversary of the death of Chinualumogu Achebe, a novelist and essayist, a man of ideas who bowed to the invitation from the Elysian Fields at 82 on March 21, 2013 at a hospital in Massachusetts, USA. Achebe died with the burden of a seer, a change agent whose literary pouch brims with warnings that can chart a new course for national rebirth.

As a man who lived and died in the service of humanity, the literary prodigy distinguished himself from his peers because of his uncanny knack for constantly peering into his country’s rabidly complex political and cultural milieu, deeply foraging into the mystical, and dwelling in the epiphanies of human experience and life struggles for churn out messages that illuminate the dark recesses of his fractured society.

So distraught was Achebe with the Nigerian system and those who run it that he chose not to connive with the ogres raping his motherland by twice rejecting national honours conferred on him.

Achebe used his works to point out the grey areas needing attention in our politics. His writings served as adequate revolution for him to articulate his people’s culture and help the African society regain its belief in itself and put away the complexes of the years of denigration and self-denigration.

This is part of his contribution to the task of giving back to Africa the pride and self-respect it lost during the years of colonialism and to seek a way to repair the disaster brought upon the African psyche in the period of subjugation to alien races.

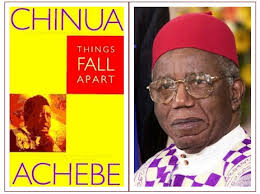

The first shot of this gift came in 1958 with the publication of his magnus opus, “Things Fall Apart”; the celebrated classic novel which became the rave of the moment, enjoying fascinating reviews across the broad spectrum of literary critics in international journals and mainstream publications.

The first shot of this gift came in 1958 with the publication of his magnus opus, “Things Fall Apart”; the celebrated classic novel which became the rave of the moment, enjoying fascinating reviews across the broad spectrum of literary critics in international journals and mainstream publications.

It was the 1958 book that defined Achebe who has about 20 books to his credit as the father of modern African literature because he appeared to have told the African story with a native Igbo flourish.

The novel depicts the life of Okonkwo, a leader and local wrestling champion in Umuofia, one of the fractional groups of nine villages inhabited by the Igbo people. In this novel, Achebe described the custom and society of the Igbos, and the influence of British colonialists and Christian missionaries during the late 19th century.

Things Fall Apart was followed by a sequel, “No Longer At Ease” published in 1960, originally written as the second part of a larger work together with Things Fall Apart and Arrow of God which came in 1964, on a similar subject. Obi, the hero of “No Longer at Ease” is the grandson of Okonkwo, the tragic hero of Things Fall Apart.

Things Fall Apart was followed by a sequel, “No Longer At Ease” published in 1960, originally written as the second part of a larger work together with Things Fall Apart and Arrow of God which came in 1964, on a similar subject. Obi, the hero of “No Longer at Ease” is the grandson of Okonkwo, the tragic hero of Things Fall Apart.

The author further recreated a new setting for Arrow of God. There are both thematic and ancestral affinities among the troika. In Arrow of God, one notices the highlight of cultural attitude with a seemingly similar theme, setting and characterization as in Things Fall Apart.

Little wonder people regard Arrow of God as another Things Fall Apart. In Arrow of God, Achebe filled the gap created in his first novel which he saw as necessary before moving into the contemporary scene.

Little wonder people regard Arrow of God as another Things Fall Apart. In Arrow of God, Achebe filled the gap created in his first novel which he saw as necessary before moving into the contemporary scene.

In doing so, he was able to portray the Igbo society under stress, a stress which is symbolically represented in the jealousy of Nwafo for Edogo, in the perennial quarrels between Ugoye and Matefi and similar actors.

Achebe completed his vivid portrayal of the beauty and rhythm of African life with Arrow of God and ventured into the contemporary Nigerian scene two years after in 1966 with the publication of “A Man of the People”, a searing political satire that stripped bare the stinking closets of the band of predators who masquerade as political leaders in an unnamed neo-colonial African country. A Man of the People captured the recklessness of politicians and the endemic corruption in the nation’s political life.

Achebe completed his vivid portrayal of the beauty and rhythm of African life with Arrow of God and ventured into the contemporary Nigerian scene two years after in 1966 with the publication of “A Man of the People”, a searing political satire that stripped bare the stinking closets of the band of predators who masquerade as political leaders in an unnamed neo-colonial African country. A Man of the People captured the recklessness of politicians and the endemic corruption in the nation’s political life.

In this book, Achebe foresaw what might eventually happen to Nigeria’s First Republic. As a seer he was, his predictions came true when the military toppled the government in January 1966.

In the book, he taught that individual honesty, integrity and greater efficiency in public affairs can transform a society when the system remains unchanged. But for refusing to heed to Achebe’s warnings in the book, what was Nigeria’s lot? Series of coups and successful military regimes that punctuated her democratic rule.

Till today, the wounds of prolonged military rule are yet to fully heal in a nation where scars of an avoidable civil war that plagued it are also open for all to see. The impossibility of abating Nigeria’s quagmire seemed to have led to the birth of “The Trouble with Nigeria;, a lucid book that excoriated the vulgarity of governance in the Second Republic during the exceptional inept administration of former President Shehu Shagari between 1979 and 1983.

“The trouble with Nigeria is squarely that of leadership” says Achebe. Despite the fact that the book coincided with the 1983 general elections, the vampires still went ahead to rig the polls, and the rest is history.

Alarmed by this dishonesty, chicanery and weakness of the political elite, Achebe in 1987 once more demonstrated his ability to predict correctly when he released his “Anthills of the Savannah”, a novel about a military coup in Kanga, a fictional West African nation.

Alarmed by this dishonesty, chicanery and weakness of the political elite, Achebe in 1987 once more demonstrated his ability to predict correctly when he released his “Anthills of the Savannah”, a novel about a military coup in Kanga, a fictional West African nation.

One thing stands the book out: expression of optimism in the ability of Africa to transcend its perennial limitations. Consequently, in October 2012, Achebe once again stirred the hornets net with the release of “There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra”. This was his last offer to the Nigerian society in his life time which tore open bitter controversies about the roles some leading characters played during the civil war. He did not intend to arouse animosity or open up old wounds, but rather to create awareness as he said, “for the unborn children.”

Six years after Achebe’s death, much of his literary advice have remained unheeded as corruption and leadership still remain the trouble with Nigeria. As a victim of colonialist piracy, Nigeria has suffered from a high degree of exploitation; as a victim of internal colonialism, she has been reduced to a veritable paradox.

Six years after Achebe’s death, much of his literary advice have remained unheeded as corruption and leadership still remain the trouble with Nigeria. As a victim of colonialist piracy, Nigeria has suffered from a high degree of exploitation; as a victim of internal colonialism, she has been reduced to a veritable paradox.

Unfortunately, the culture of impunity occasioned mainly by power aphrodisiac has opened the floodgates for plundering government’s till. There is wide spread acrimony arising from visible inequalities and social disorder, intolerance, mistrust, bigotry, unhealthy propaganda, deepening hatred and hate speech, rapid deterioration of relationship between the peoples of the different geopolitical zones and other myopic sentiments.

There is a wide margin between the powerfully endowed politicians with sophisticated wealth and the educated and non-educated poor of the society. All these could form a catalyst for a revolution; a revolution which will take a measure where the poor will not only demand for their share of bread but commandeer it.

It will be sudden and involuntary. There will be no leader of the rebellion or anyone directing them to act. Hunger and the survival instinct will be the propelling force. And by then, the so-called affluent in the society will either be compelled to examine the plight of the poor or flee from their wrath.

The situation appears to be quite like an earth tremor signalling a dangerous earthquake. The only way to abort any upheaval or revolt of the poor is for the wealthy leaders to heed to Achebe’s call by turning a new leaf and beginning to spare a thought for Nigeria’s less privileged. Rest in peace, Chinua Achebe.

No comments:

Post a Comment